‘A new normal’ is perhaps the most uttered term during this COVID 19 outbreak. It advocates the idea of fundamental change being an adaptation mechanism against this global crisis. The terminology is not new in the discourse of sociology, political economy and disaster science and often refers to the ‘new consciousness’ seeking answers for what was wrong in the system previously considered to be ‘normal’. An immediate response to this new normal is evident in the forms of widespread measures of ensuring social distancing, washing hands, covering the faces and so on. These health measures have significantly altered the way we used to live, work and communicate regardless of what professional niche we belong to. For every professional, it is important to acknowledge that the (re)assessment of their form of duties is necessary not only for finding ways for temporary adjustments but also for the long term stability of the niche itself. For the architect community, this ‘new normal’ can be characterized as the push for a paradigm shift – a movement to reshape the discipline (both education and practice) to fit in the context of Bangladesh. Perhaps, with numerous webinars and online discussions, such transition appears to have gathered momentum during this pandemic.

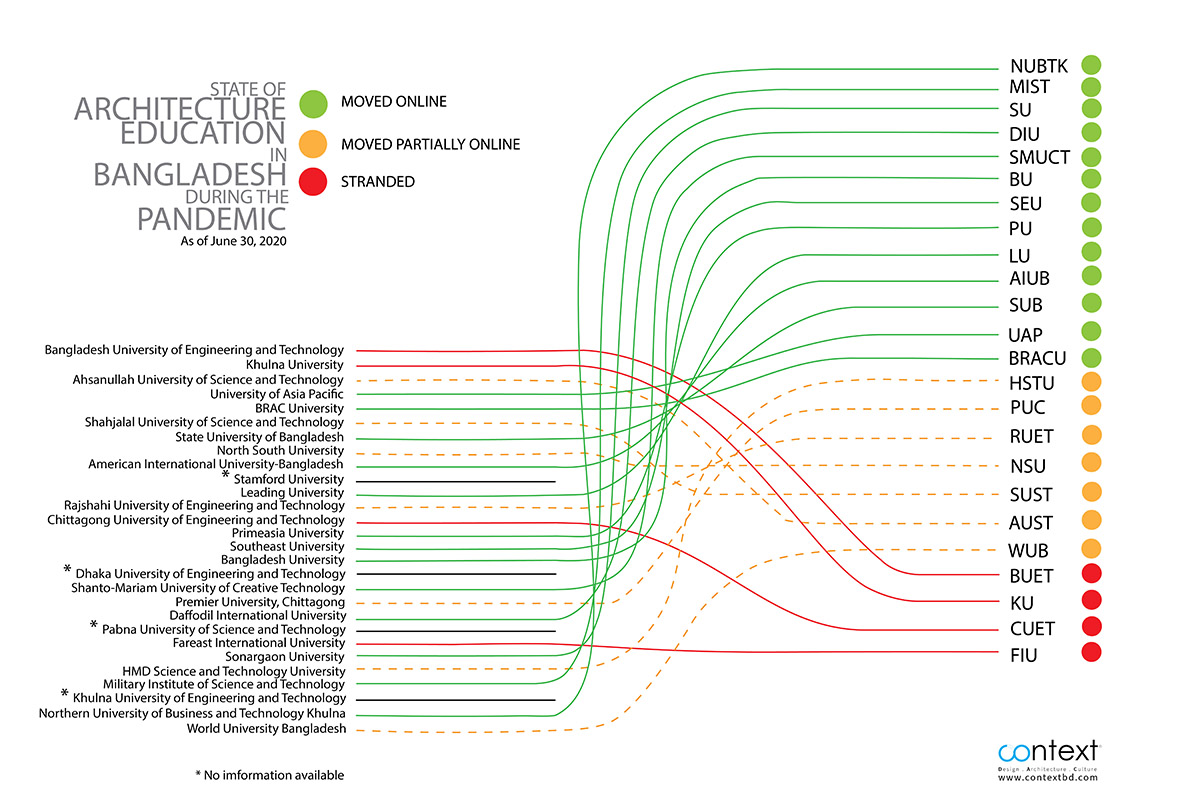

In architecture education, the transition can be observed in ways of conducting the design studios which is an inseparable aspect of it. Teachers and students are quickly adapting to an online learning environment. Technologies to facilitate students to continue their work are being discovered, mastered and accepted in no time. Though in a rudimentary stage, its success is not undisputed and there is growing dissatisfaction among students (and parents) about the quality of this online education. The growing criticism may open doors for revisiting the teaching methods and techniques to explore how the online learning experience can be improved to accommodate the intricate ways of course delivery. And isn’t it true that practices like conducting the design reviews and thesis jury by video conferencing would seem like a complete travesty in the time before this pandemic? But this crisis has made it happen and proved the chance of rethinking different aspects of our traditional pedagogical system to address the upcoming challenges.

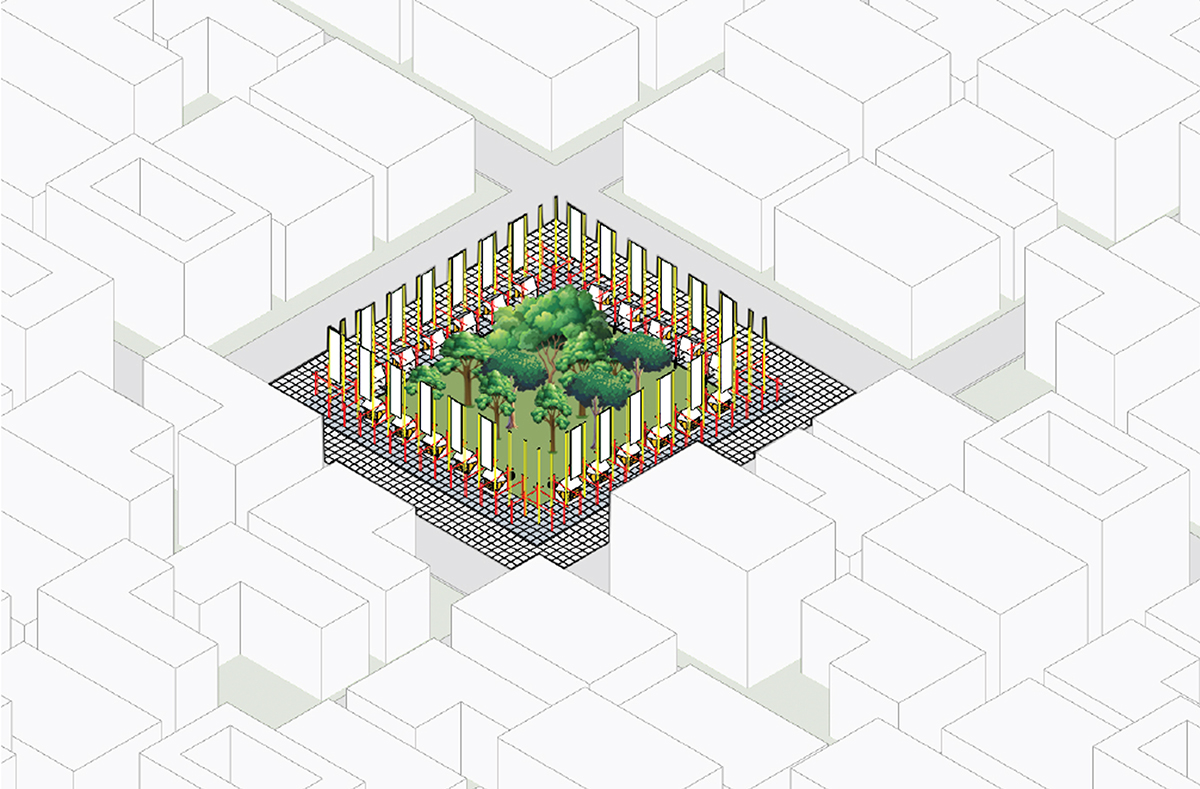

While impromptu online learning methods are trying to find its way, it cannot be denied that this is merely the utilization of tools and adaptation of technology. But in the long term, this adaptation denotes the possibility of initiating a process to go in deep to find the opportunities to rectify what was wrong in the previously normal scheme of our pedagogical culture. As architecture students learn to design how people interact in a built environment, there might be the need to design how not to interact in a pandemic situation like this, who can tell? Aspects of public health, epidemiology and virology might need to be integrated into the curriculum. Creating a more efficient and horizontal exchange of knowledge with other disciplines with acceptance of new ideas might be the key to confront the challenges. In order to produce efficient and specialized professionals for a situation of crisis, self-motivated learning needs to be nurtured sensitively so that young professionals can assist the larger community instead of taking the capitalistic route of serving rich clients only.

Furthermore, as a professional community, the architects have responded to this situation by adopting measures like ‘working from home’ for quite some time. Again, if we look at the ‘previous normal’ of the office culture of architectural firms, ideas like this would not be accepted easily. However, this global health crisis has put us in a situation to find ways to get along with it. This justifies that we should look for solutions towards a ‘new normal’ which may seem unorthodox at first but will ensure the resiliency of the professional practice of this community in the long run. The professional body, Institute of Architects Bangladesh (IAB), has taken some rapid and significant initiatives as an emergency response. For extending emergency medical and financial services to its members, they have collaborated with hospitals under which the members, their families and staff will receive certain medical services with special discounts. The institute has also announced services like Emergency Finance Scheme (EFS) enabling its members to take interest-free loans. Within its limited organizational and financial capacities, the institute is constantly working for the betterment of its members. But will it be enough in the long run if the effect of this global pandemic continues for an uncertain length of time? Will these relief-oriented, retrofitting activities be enough to instigate necessary transformation in the profession to sustain and grow in the pandemic world?

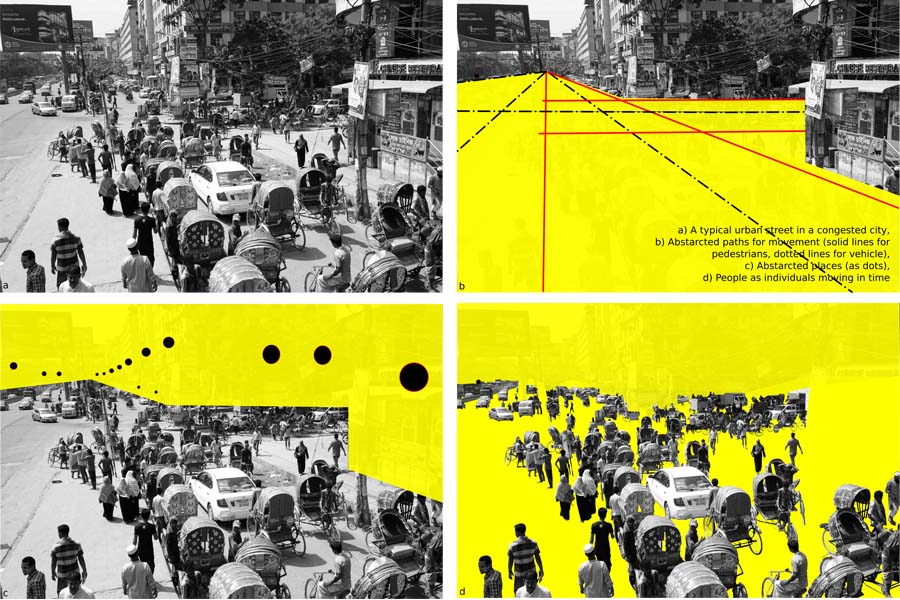

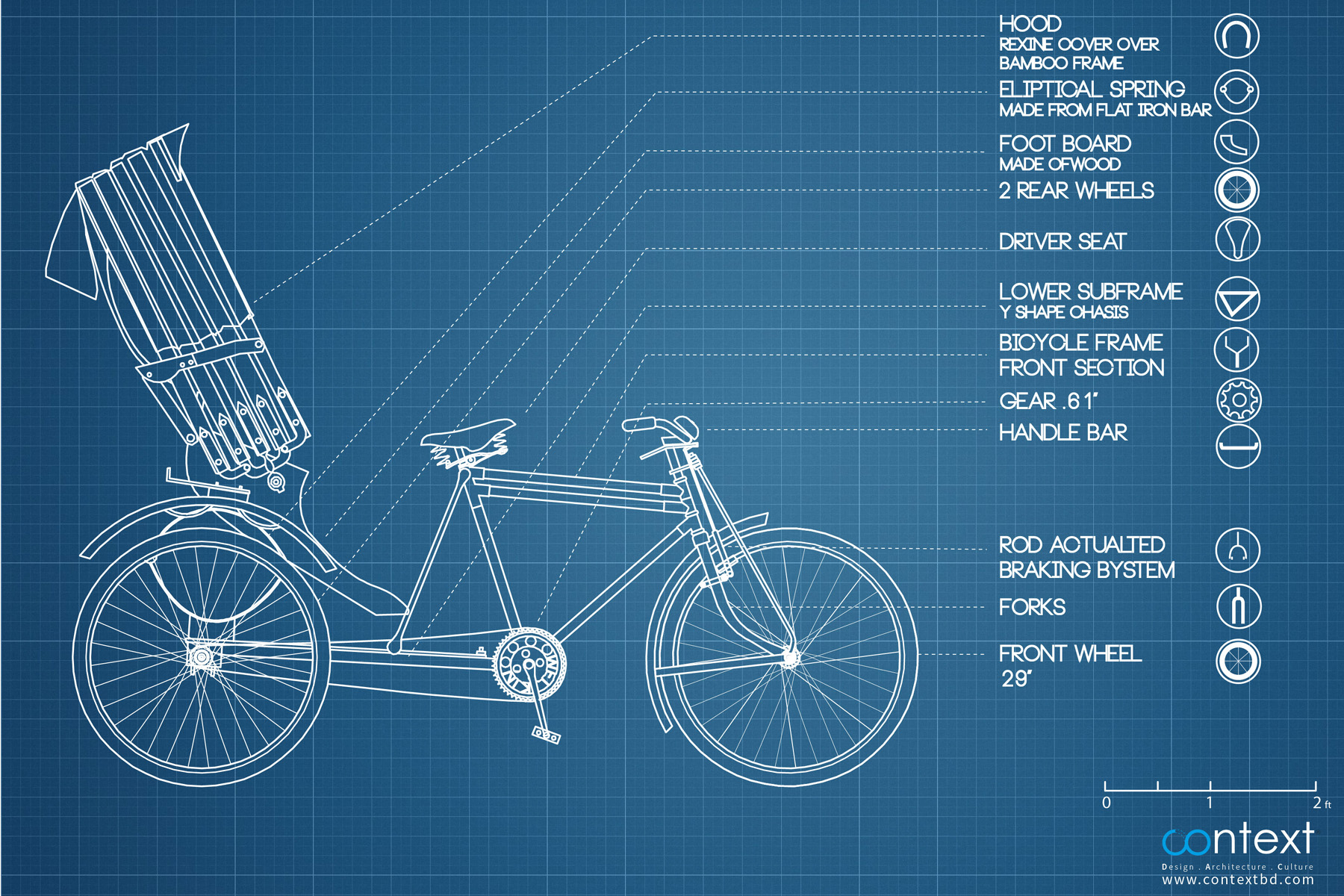

It can be assumed that amidst this global threat of the COVID 19, the built environment professionals are in an existential crisis as the top priority is not given to this sector as an essential professional service at the policy level of the government. Here comes the question that have we failed to establish our ‘value’ to the societal and political process? An evident large discontent among the fresh graduates and students about the significantly long process of architecture education and then not being able to efficiently contribute to the professional field can further question the existing ‘architecture education model’ which is tied to the need of the 19th century ‘industrial revolution’. So, isn’t it necessary to mass democratize the schooling model so that education can be brought down to our context allowing people to actively engage at the grass-roots level? Do pedagogy and profession need to be rethought according to the changing realities which can strengthen the built environment professionals to caste a strong impact on the society and valuate their position more effectively?

Finally, it’s undeniable that industry and institutions are closely contingent upon one another asking for a sustainable adaptation method which will mold and prepare the field itself to deal with crisis situations in the long run. Changes in one sector can effectively influence another. We have to ask ourselves, are we realizing that experimenting with new ideologies can result in something good or at least can open the door for further discussions? Isn’t it necessary to ameliorate the radical typologies in pedagogical and professional practices to address the challenges of a new normal? As the built environment does not involve architects only, isn’t it necessary to establish a transdisciplinary dialogue with other disciplines like sociology, anthropology and epidemiology? A horizontal exchange of knowledge can effectively impact the scenario as a whole, but does our current practice allow it enough? Is ‘lack of acceptance’ being the major hindrance to explore the possibilities?

In light of these questions, maybe the key to an effective long-term response lies within the realization whether we are expecting to go back to the previous normal or we are aware of the fact that ‘a global paradigm shift’ is imminent where we have to identify and rethink our outdated pedagogical system and professional practices which are due for some revolutionary changes for a pretty long time.

[1] Guy Debord, (1960) “La Société du Spectacle”/ “The Society of Spectacle”.

About the Author:

Anupam Bose, graduate, Discipline of Architecture, Khulna University

The article is primarily based on the discussion held as a part of the online symposium titled Towards a New Normal: Rethinking Architecture and Urbanism in the Pandemic World. Dr. Muntazar Monsur (keynote speaker), Dr. Fuad H. Mallick, Ar. Jalal Ahmad, Dr. Farhan S. Karim, Tanzil Shafique were the discussants among others.