Tangible and Intangible Cultural Heritages exhibit and encapsulate popular memories of the city through a complex interplay of production, consumption, re-construction, interpretation and diverse tactics of remembrance – a comprehensive observation by sociologist Anouk Bélanger. Every time the wrecking ball unceremoniously razes off an old building, chunk of our history and identity is forever wiped off from the earth’s surface. Do our past not deserve a future? More importantly, can our past ensembles coexist with the rendition of our future development? Unsettled agitations as such led to the launch of two competitions followed by an online symposium “Cities in Transition: preserving our past, building for the future” in the first quarter of 2021. By engaging people and built environment professionals, the collective events aimed at raising public awareness through heritage appreciation in order to reinforce a sense of identity and continuity in a fast-changing world that we live in.

In the march of progression, where economic rationalism seems to dictate the fate of our cities, built heritage management is often perceived as the “hindrance in development opportunities”. Often times, we bulldoze old structures and landmarks to make way for swanky new buildings without being critical of its consequences. Such act is far more lethal than the mere losses of brick and mortar, threatening the city’s heritage and landmarks that are strongly associated with people’s memory and image of the city.

Protection of Cultural Heritage: Global Perspectives

The destiny and the future of us all in the world are increasingly intertwined as we face global challenges unprecedented in terms of numbers, dimensions and severity. Since our capital Dhaka is going through a phase of re-development and time-space compression in terms of cultural protection, we ought to go along with the tide of times and rise to challenges by leaning on to global strategies, collaborations and good practices. Professor and UNESCO Chair in Intangible Heritage, Filipe Themudo Barata stressed on two institutes that deal with the cities in transition; UN-Habitat which deals with cities and issues such as explosive urban growth in Asia and the changes of demographic profile in cities, and UNESCO, which talks about the ease of our memories being lost in metropolis as cities convene towards a heterogeneous narrative in contrary to the past homogeneous situations. This occurs particularly due to the displacement of people from the stability of a horizontal society towards the mobility of a vertical organization. All these have influences on our collective memory. Filipe further encompasses on what such movements do to the existing construct of a city and its culture as it now must house diversities in culture which takes dozens or even hundred years to establish. He sees possibilities of establishing new policies in a city through negotiation with the policymakers and the inhabitants that might help preserve the collective memories of a city. Collective memory relates to multiple narratives and architectural heritage sits intrinsically at the intersection of multiple narratives as palimpsest. This is where a very good relationship is found between tangible and intangible heritage which has been extensively discussed by Dr. Mizanur Rashid. In reality, the phenomenon becomes more complicated questioning what is borrowed, authentic and reconstituted as identity/heritage through time and space. In his presentation, he argues for the need for a new theoretic framework and re-centering our position to interpret the past. His prolific speech leaves us to wonder whether we are inclusive enough to acknowledge the osmotic process of heritage creation that absorbs, shares, borrows and reconstitutes narrative through time. Preservation of Intangible heritage, as well as associated legislation and institutional practice, is relatively new and yet to be adopted in many parts of the world, whereas the same of tangible heritage has gained quite momentum over time. Architect-Planner Nigar Reza, who is a senior policy officer in Commonwealth Heritage Team, described the Australian government policies as an international case and how Bangladesh may look upon them regarding the preservation of heritage to begin with. She suggests how we may convene to the practice by learning about the existing status and gaps, listing and knowing the authorities involved. She further stressed upon generating public awareness and establishment of the legislative framework in order to make it happen.

Built Heritage in Bangladesh Context

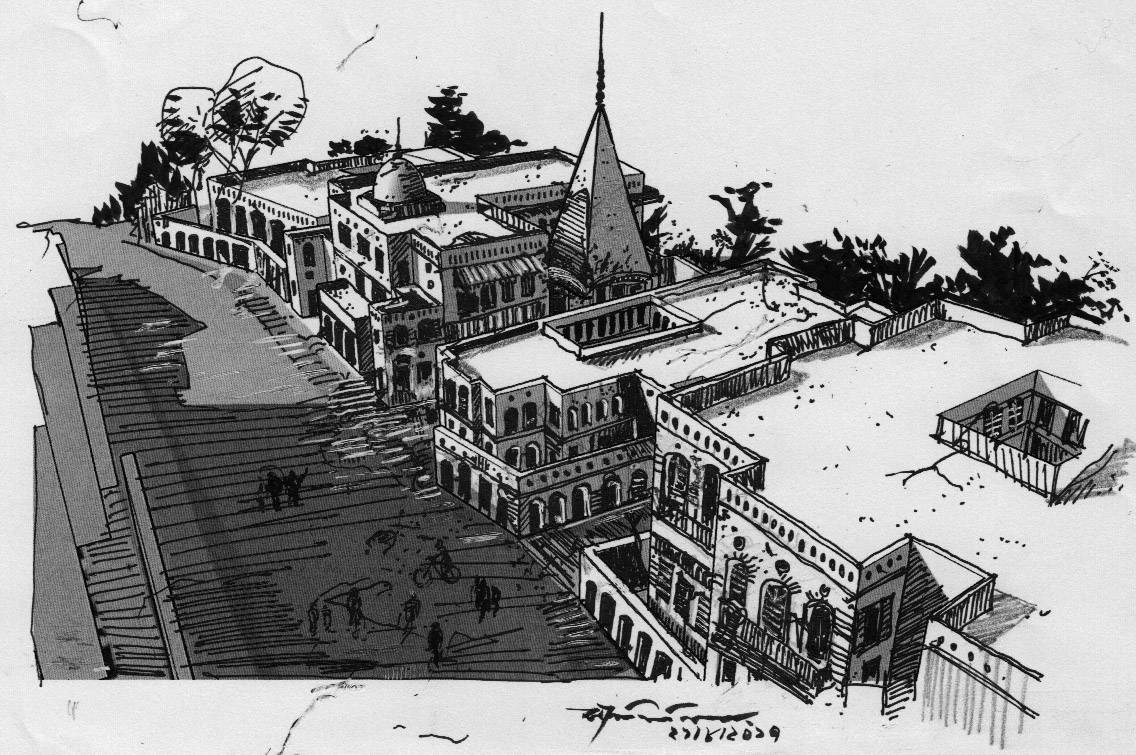

In a country like Bangladesh, where the population is explosive while land and economy being scarce, sparing funds to conserve built heritage is often perceived to be a “drain in the society”. The underlying ideology that heritage conservations are mere extravaganzas and not an asset or an investment seems to dominate the minds of the majority. The scenario becomes more acute when stakeholders like elected people, local leaders bother less about the values and future of these heritage buildings and their cultural context. For them, ‘future’ is a nebulous concept which does not march past the periodic political timeline, followed by the re-election cycle. A deep-rooted connection has been observed between institutional negligence and derelict traditional settlements. Some of the institutional drawbacks include inadequate management plans, legislative and regulatory frameworks, biased political and economic interests to safeguard both intangible and tangible assets of urban heritage. Through a series of magnificent illustrations, Dr. Sajid Bin Doza exhibits the traditional areas (particularly the historic city of Rajshahi) which are getting dilapidated due to the carelessness of the administration and authority. He grieves on the loss of the certain patterns that the traditional towns were built around and the sequence of realms that allowed inhabitants to perform daily activities and lively interactions. The organic sequence is now being out shadowed by the gridiron pattern of planning which does not quite seem to connect to the memoir of these places with the dwellers within. This as a result leads to pretentious cultural practices and knowledge gaps, as inhabitants are very unaware of their city’s histories and past. Institutional capacity must address the importance as well as the threats and challenges arising from lack of availing the traditional techniques, building materials and craftsmanship. Being in the field for much of the past, Professor Abu Sayeed aligned the renditions of pen and paper to the reality of the practice. Pioneer in the heritage conservation management in Bangladesh, Sayeed suggested that we see each conservation process as opportunities to enhance skill-building roles for the masons and craftsmen and revival of original technology. However, in the light of his in-hand experiences in the country, he fears that the traditional building materials used in building heritages are now about to reach extinction. He shared the challenges that he had to face in the field. Some of them are: Lack of research in Bangladesh about the knowhow of traditional architecture, methods and its practice; Lack of skilled craftsman, lime mason, chinnitikri mason, brick dresser, etc.; and Scarcity of traditional methods and materials which are being replaced by new techniques.

Way Forward: Beyond Preservation

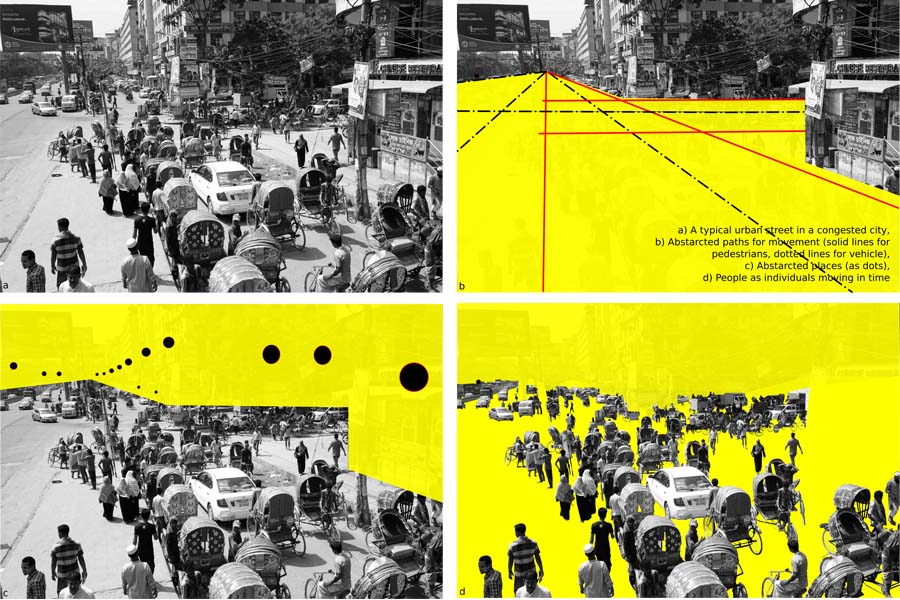

As the discussion now zooms out to bring agendas out from the institutional framework to the public domain, much has been discussed about the likability of the public domain to potentially become a way forward to our future interventions to do justice to our treasured past. Carrying forward the eloquent observations made by Dr. Rashid and Professor Sayeed, Adnan Morshed, Professor at the Catholic University of America, shared his thoughts based on what he has seen and understood in the wake of the conversation that was going on since the specter of demolishing TSC and Kamalapur Railway Station. Morshed hunched that the production of knowledge ought to operate in two layers; decolonizing knowledge production and internalizing it whatsoever. He argued the need for curricular reformation as an integral part of the experimentation that education allows and gets past the semantics of the colonial framework of education. He further suggested that unless we bring historic preservation with some economic incentives, it is not going to work. He further weighed in the significance of the public domain of heritage preservation and encouraged the younger generation to participate in the knowledge gap and democratize the knowledge production in the process. Lastly, Humaira Zaman, a prolific conservation activist and an architect, highlighted the challenges she thinks should be considered when discussing heritage conservation in Bangladesh. Devoid of policy implementation in practice of heritage preservation, lack of knowledge, resource and interest, we are constantly losing our ancient artifacts. The lack of awareness and jurisdiction on the national level results in jeopardy and vandalism of several past structures of great importance. In order to safeguard our cultural heritage, we need to edify our future generations and ensure that the heritages are relevant to the aspirations of the present-day communities.

SDGs of the United Nations give light to the growing consensus that the future of our societies will be decided in urban areas in which culture plays a key role. The sustainable management of heritage buildings, sites, and their cultural context are going through a process of change both in theory and practice, with a shifting focus on isolated built heritage assets towards a landscape-based approach (adopted by UNESCO as HUL). The emerging population is changing the profile of the cities as it is now more heterogeneous than ever before. Immigrants and foreigners generate new heritage and culture. Heritage is therefore not static. However, the changes should be condoling and beneficial to the country as it is a part of the social development. For this to occur, we must refrain from objectifying our heritages as that is when we can easily trade it off. The significance of heritage conservation should be brought forth to the public domain while involving all the stakeholders and incorporating some economic incentives along the way. It is obligatory for the heritage professionals to demonstrate the relevance of historic preservation and break free from the stigmas of the aforementioned being the luxury of the “chattering class” but establish it as an integral part of the community at large. Conservation is out beyond the mere preservation of façades, freezing the building in time. By favoring restoration over the replacement of both tangible and intangible artifacts, we can retain our identity, promote cultural tourism and reduce demolition waste besides preserving the ambiance and character of a living piece from the past that accentuates social cohesion and wellbeing of the community.

About the Authors:

Sadequl Arefin Saif | Research Assistant, BRAC University.

Shajjad Hossain | PhD Researcher, University of Évora, Portugal.

Illustration: Dr. Sajid Bin Doza | Associate Professor & Head, Department of Architecture State University of Bangladesh.

Endnote: The online symposium “Cities in Transition: preserving our past, building for the future” was jointly organised by ContextBD and Bangladeshi Architects in Australia (BaA) . The recorded session of the symposium can be viewed here: