PART 01

By definition context refers to the setting of an idea, text, statement or form, in terms of which it can be understood clearly. For an urban architecture, the context is the surrounding environment and its various constructions – physical, social, economic, ecological, cultural and so on. Within the context the (re-) new work of architecture is supposed to be weaved in an integrated way. The complexity that arises while discussing urban context of architecture is that architecture creates and recreates context through both its ‘closeness’ (architecture as bounded object) and ‘openness’ (architecture as ‘space’ — related to all other spaces). This article, however, will focus mostly on the analysis of open characteristics of architectural spaces, while recognizing its ‘relative closeness’.

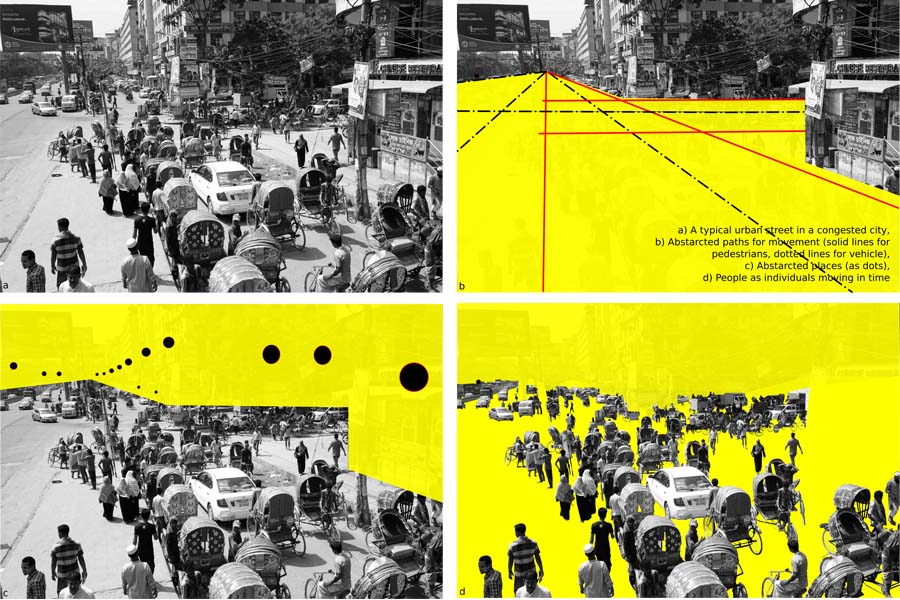

It is of no doubt that rigorous analysis of surrounding physical environment is important for better understanding, or rethinking of, any context. In this article I argue that, in an abstract sense,urban physical context can be analyzed across three key matrixes among others—place, path and people. Place refers to any space that people identify as a unit. Paths are connecting spaces among and between places. People form a particular kind of space that has direction in space-time.

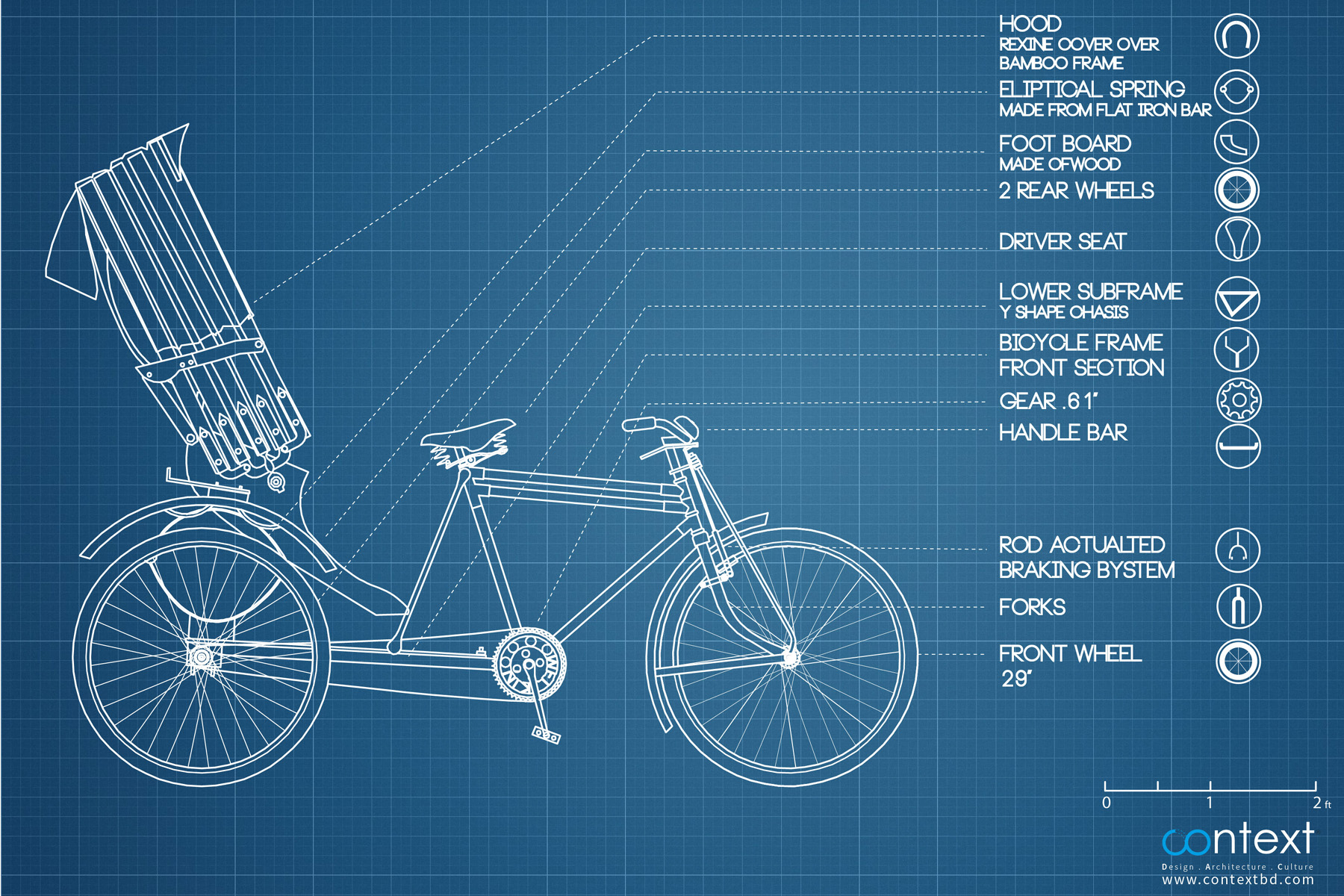

Place, path and people can be measured objectively while these are open to subjective interpretations. For example, while places can be identified as dots in space, sense of place differs from building to building. Paths as ‘geometric lines’ between or among two or more locations are quantitatively analyzable; however different paths might symbolize different meaning in particular context. Similarly, people’s movement can be studied as space-time vectors while their preferences are difficult to understand without cultural studies. In cities,place, path and people form interconnected systems; not discreet ones. It is to be noted that historically interrelations between place, path and people have been an ignored topic in architecture, transportation planning and social sciences. These disciplines show profound mastery in studying the elements of place, path and people separately. In case of architecture, the focus has been on place-making, where paths and people are taken for granted. Transportation planning identifies roads and streets as autonomous entities, which is not true. Social sciences focus on people, where place and path are assumed to be the innert background, which obviously is not the case in cities.

Given such background discussion, this article will argue that lack of understanding about the interactions between people, path and place is one of the major gaps in understanding context and architecture.

From urban design perspective, let’s understand place, path and people in terms of scale, diversity and accessibility. In terms of scale, spatial design problems vary in different urban scales due to the degree of interacting forces among place, path and people.In that sense, a‘city’ is nevera ‘big building’. For example, analyzing spatial configuration of a staircase is relatively simple within a private residence where as spatial analysis of a foot-over-bridge can be extremely complex in dense urban areas. Although small in scale, a successful foot-over-bridge must fit properly within the transportation network and public movement pattern. This demands enormous analytical study at a greater scale than the scale of the to-be-designed form.

As about diversity, urban spaces and buildings are hardly of homogeneous use. Different types of activities of different people group intermingle in the same space (mixed-use spaces, plazas, streets, parks, play spaces etc.). While a mono-functional space can be designed with traditional wisdom or standardized codes, forms of contested and multi-use spaces demand continuous reevaluation of the interactions of place, path and people.Many of such interactions are emergent, rather than stagnant. Interactive outcomes of place, path and people can be considered more like the embryo of an egg; not only the shell. The shell, although very important, is a temporary state in the process of life. But see, the ‘embryo’ reminds us of potentials of life.

Broadly, accessibility means people’s freedom to move from one place to another through paths within space-time constraints. In cities, people hardly remain confined within their neighborhood. And people mobility behavior varies across age, gender, income group and so on. Thus, accessibility of an urban space depends on its connection to all other spaces. Even, if the connections are right, it also depends on people’s preferences as well (i.e. whether people like to have access to that space or not).

The above understanding of urban space involving place, path and people negates ‘closed-site’ as core-ground for making architecture.A site is both closed and open. Such statement however introduces some practical complexities in architecture. For example: in terms of scale, decisions on the surrounding urban environments are often beyond the domain of architects and urban designers working in a particular project. About diversity, it is challenging to include heterogeneity of activities during spatial design. Question might arise: How to find sizes and shapes for an urban plaza in a participatory way, if people drastically differ in their opinions and if their opinions change over time?Regarding accessibility, complex problems might arise in understanding street hierarchy. For example, vehicular streets,although they enhance accessibility for the car owners,reduces accessibility to nearby opportunities for pedestrians, children and elderly.

Given the practical complexities are addressed in different degrees in practice with due insight, the place-path-people approach for understanding architecture and context together demands attention. However, it should be noted that call for studying socio-spatial context in finding form for architecture is not new (See, Venturi, 1966; Schumacher, 1971; Jacobs, 1961; Broadbent, 1973 for example). Also, abstracting the urban built environment with few key elements for analytical and theoretical purposes is not new (See, Lynch, 1960, Hillier and Hanson, 1984 etc.). This article adds that while analyzing socio-spatial context place-path-people can be three important dimensions for analysis specifically to address spatial qualities, such as accessibility and diversity, at different urban scales and for different group of people. Place-path-people view also creates possibility for utilizing state-of-the-art computation technologies – gifts of the 21st century.

Also place-path-people approach can help understanding physical urban context in rapidly urbanizing cities. In this regard, I will briefly share some of my personal observations in the urban context of Dhaka while highlighting the relevance of place-path-people approach.

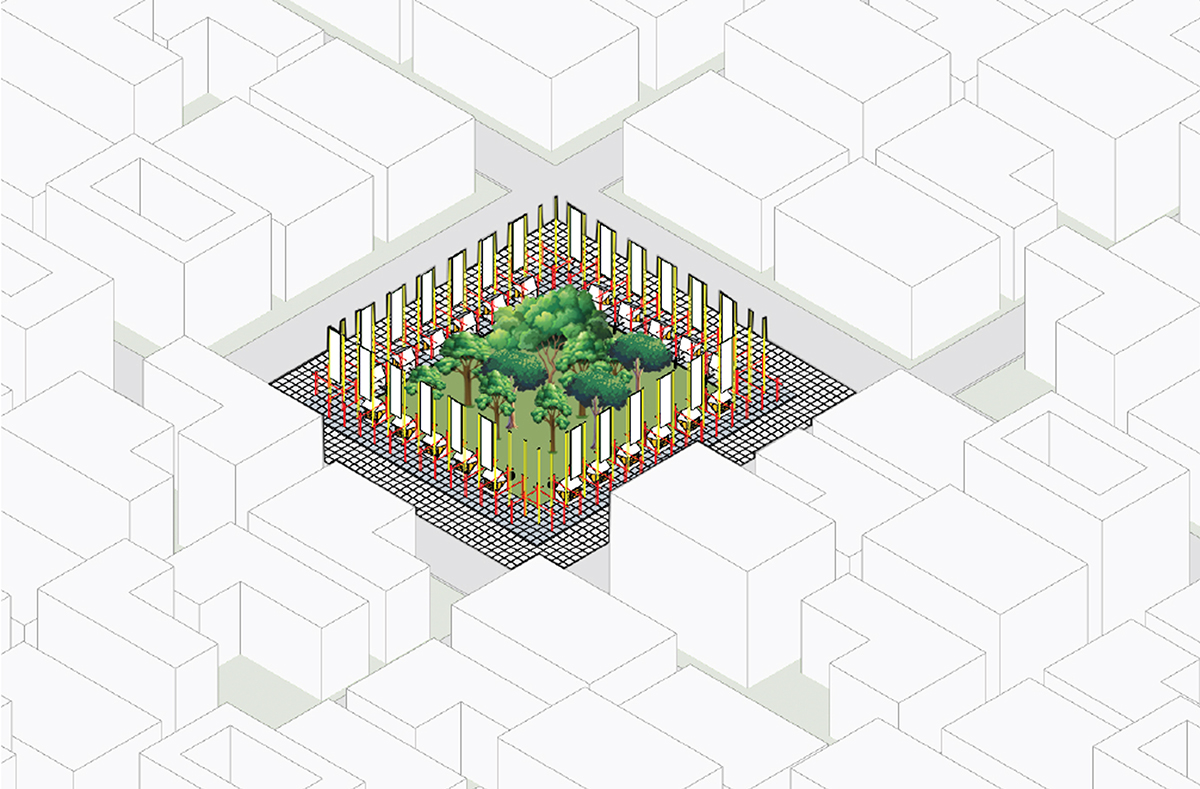

In my view, present architectural and planning practices in Dhaka inspire the idea of an ‘island-context’. Plot-based, guarded, gated and multi-storied apartments in Dhaka are some easily recognizable elements of the islands. The ‘islands’ seem to be ‘blind’ to the surrounding places, paths, and most importantly, to people’s lively interactions in space.It can be argued that an island-context is a product of miss-matched interactions between places, paths, and people. Presumably, while designing buildings within island-context, the designer assumes a closed-site. The point of departure here is to ask whether place, path, people is worth giving an attention in architectural and urban design studies and how their relations can be well studied during design process to address the adversaries related to the built environment.

Pragmatically, do the place-,path- and people-based understanding suggests any direction? The first direction is an emphasis on socio-spatial research in architecture, urban design and planning. Such research should be multi-disciplinary; and should encompass both quantitative and qualitative perspective. Second,recent developments in computational modeling (such as GIS and CAD systems) can be explored extensively to simulate complex relations between place, path and people.

READ [PART 02] Accessibility of Children Play Spaces in Dhanmondi : A Syntactic Study

Works cited:

Venturi, R. (1977) Complexity and Contradiction in Architecture, New York: Museum of Modern Art.

Schumacher, T. (1971) Contextualism: Urban Ideals+Deformations, Casabella, 359-360, p. 79.

Jacobs, J. (1961). The Death and Life of Great American Cities. New York: Random House.

Broadbent, G. (1973)Design in Architecture: Architecture and the Human Sciences, Surrey, UK. (PP. 73-86)

Lynch, K. (1960) The Image of the City, The M.I.T. Press, UK

Hillier, B and Hanson, J (1984). The social Logic of Space, Cambridge University Press.

About the Author:

Bhuyan, Md Rashed is an architect, urban designer and researcher. Currently, Bhuyan is a PhD research scholar in the Department of Architecture at National University of Singapore (NUS). He is also a Lecturer in Architecture (on study leave) in the University of Asia Pacific (UAP), Dhaka.