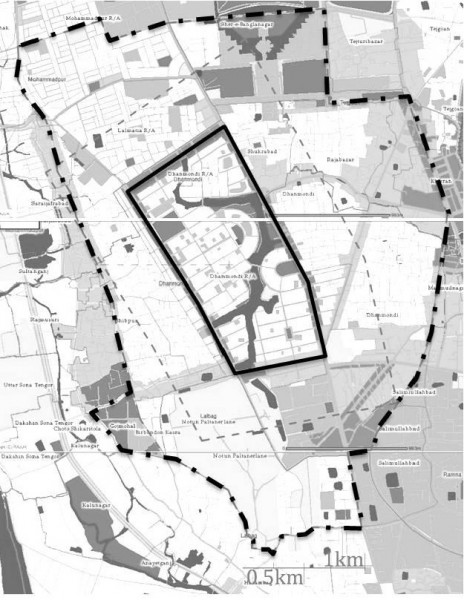

The following analytical study evaluated accessibility with reference to the notion of topological space in space syntax. In such notion, urban space is represented as a single system of interconnected lines. Different urban spatial qualities (in this case accessibility) then are evaluated with reference to the syntactic values of those lines.

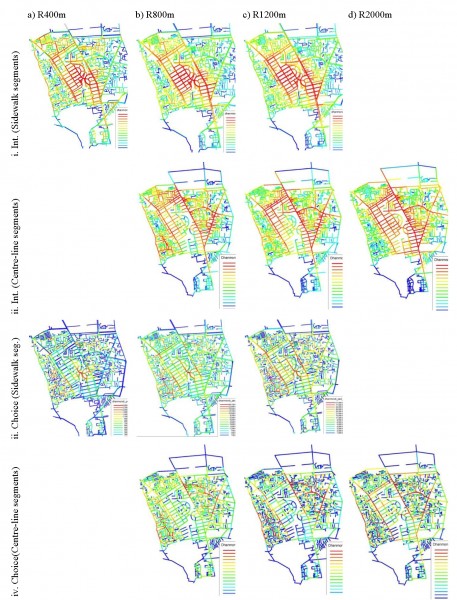

Results from the syntactic study across 400 meter, 800 meter, 1200 meter and 2000 meter radius are presented in Figure 3. Pattern of integration of sidewalk segments shows that the streets near Rabindra Sorobor, Mirpur Road near Science Laboratory and Shat Mashjid near Road 9a, forms the most integrated places in the system (colored red and yellow in 2ia, 2ib, 2ic). That means, possibility of pedestrians using the paths and places near these paths will be higher in intensity than other areas in the system. Pattern of integration for centre-line segments shows that long stretches of Mirpur Road, Shat Mashjid Road and Green Road are the most integrated segments. That means possibility that all people (including vehicles) using these paths is higher than other segments in the system (colored red and yellow in 2iib, 2iic, 2iid). Overall, pattern of integration of sidewalk segments also shows that the most integrated line segments are located within DRA as compared to the surrounding areas such as Jigatola and Kalabagan.

Pattern of choice of sidewalk segments shows a mosaic pattern of higher and lower values throughout the system. That means, possibility of pedestrians passing through the streets are quite evenly distributed. Within DRA, the bridge linking two sides of the Dhanmondi Lake (Road 10 and 8a) and the front street of Sultana Kamal Women’s Complex show high choice value (colored red and yellow in 2iiia, 2iiib, 2iic,). Pattern of choice of centerline segments shows that adjacent areas surrounding DRA, such as Kalabagan, Jhigatola, show greater potential for all types of movement (including cars) as compared to the internal streets of DRA. This is possibly due to the longer segments in DRA (which is a planned development) compared to the shorter segments in the surrounding areas (which are non-planned developments).

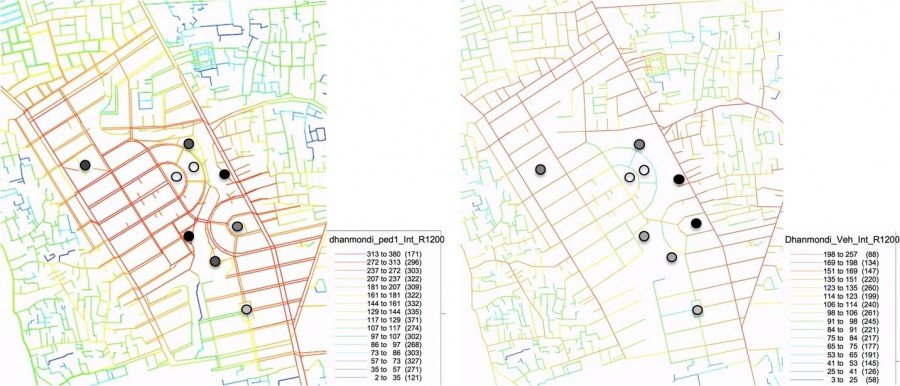

Accessibility of play spaces in DRA was measured by extending line segments from the entry gates into the playgrounds and parks. Figure 4 shows the relative accessibility of the public play spaces for both sidewalk- and centre-line segments. Considering sidewalk-line segments, the Rabindra Sorobor Park Area along Dhanmondi Lake shows highest accessibility followed by the Kalabagan Playground, Abahani Playground and the Road-8-Playground (marked from darker to lighter dots in Figure 4a). When the centre-line segments are considered the playgrounds along the Mirpur Road shows higher accessibility (Marked darker in Figure 4b). It is interesting to note that pattern of pedestrian and all-movement accessibility of the play spaces varies within the system. For example: The Rabindra Sorobor Area along Dhanmondi Lake shows relatively higher accessibility only with reference to the pedestrian segments whereas the Road 8 Playground and the Kalabagan playground show higher accessibility in centre-line analysis. This implies that while designing or redesigning play spaces it is necessary to study pedestrian and vehicular movements separately in the urban context of Dhaka.

However, while measuring accessibility of play spaces for particular group of people (such as for children), some limitations arise. For example, in this study the syntactic measures ignored the attractiveness of play spaces (such as size, surface quality, provisions of facilities, naturalness etc.). Nevertheless, possibility of interactions in play spaces will be expectedly affected by the attractive attractiveness of play spaces. However, few methods attempt to measure attractiveness of urban spatial opportunities quantitatively. Gravity model developed by geographer Walter Hansen (1959) is one among those few methods.

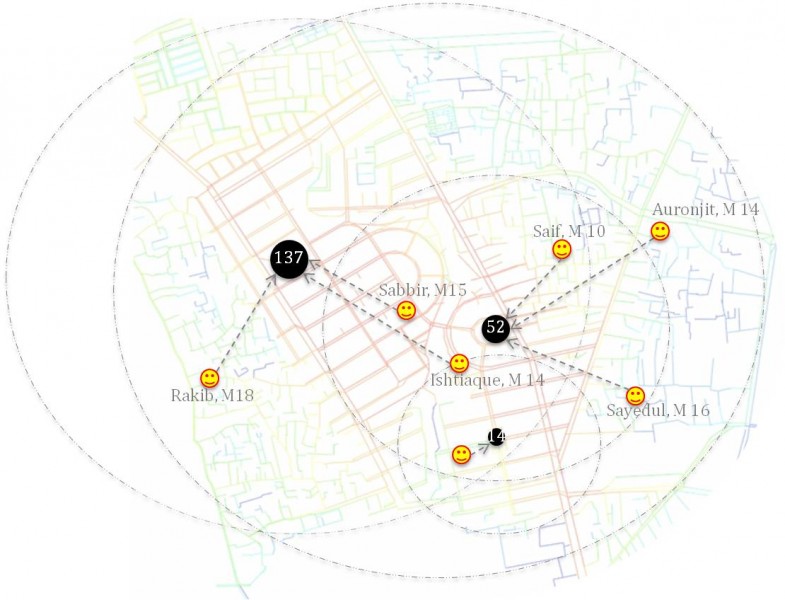

According to gravity model, while measuring accessibility of play spaces, relative sizes of the spaces and other ‘distance-decay’ factors (Hansen, 1959) need to be considered. For example, in Dhanmondi Residential Area, the Abahani Playground is 12 times bigger in size than the Road 4 Playground. This might significantly affect accessibility pattern of the play spaces beyond the configuration of the paths. This assumption seems valid. During our field study, some of the users (children aged 10 to 14) at Abahani Playground mentioned that their house is located more than one kilometer from the playground, whereas, children in the Road 4 Playground reported that they live within few hundred meters from that playground (Figure 5). Thus, in the context of Dhaka, it is important to consider the effect of decaying distance (i.e. opportunities near one’s house has higher attractiveness than opportunities located far from one’s house) while designing catchment radius.

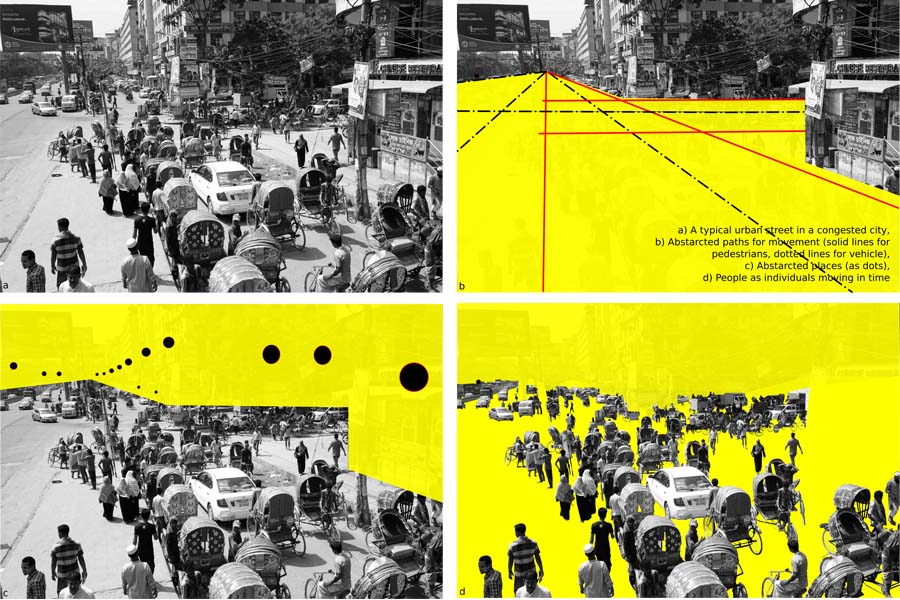

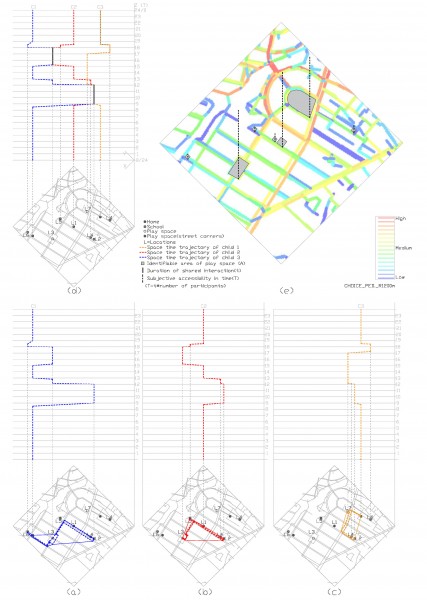

Another aspect related to measuring accessibility of play spaces for children is that Children’s preferences for urban play opportunities might be influenced by social factors such as their age, gender and family background (Aarts et al. 2012; Islam, 2008). These are mostly people based factors that changes over time (i.e. different in different times of day, week, month, year etc.). Figure 6 graphically shows that possible pattern of three children using different formal and informal play spaces will vary across times of day. This space syntax based study however did not distinguish the people factors in its analysis.

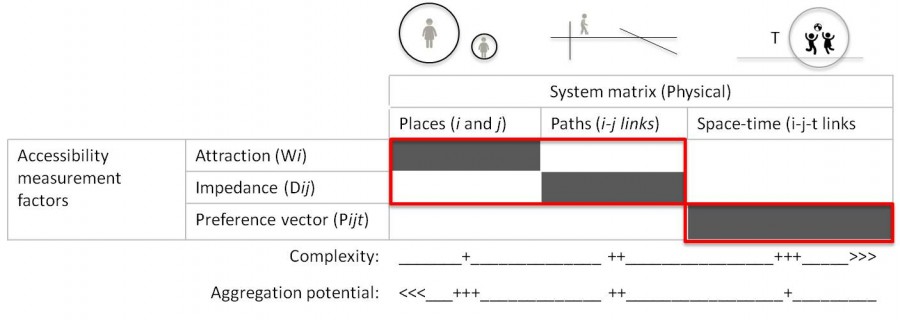

Thus, from the above discussion it can be summarized that accessibility measured across path network (i.e. by using space syntax measures), would provide a useful, but generic, representation of children’s accessibility to play space. Explaining accessibility for specific group of people in urban space can be well improved through a combination of other accessibility methods, (such as gravity method which is place based) and behavioral models (such as agent based model which are individual based). From such understanding, Figure 7 shows an outline for measuring accessibility of play spaces for children in three dimensions, namely place, path, and people. Being flexible in its measure, a combined model might have better implication during policy, planning and design in Dhaka.

READ [PART 1] Architecture and its Urban Context: Place, Path and People

Works cited:

AARTS, M., Vries, S. I. D., Oers, H. A. V., Schuit, A. J. (2012) Outdoor play among children in relation to neighborhood characteristics: a cross-sectional neighborhood observation study, International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity, 9(98).

HANSEN W. G. (1959) How accessibility shapes land use, Journal of the American Institute of Planners, 25:2, 73-76.

HILLIER, B. (2012) The genetic code for cities: Is it simpler than we think?, in J. Portugali et al. (eds.), Complexity Theories of Cities Have Come of Age, 129. DOI 10.1007/978-3-642-24544-2_8, Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg.

HILLIER, B. AND HANSON, J. (1984) The social Logic of Space, Cambridge University Press.

HILLIER, B AND PENN, A (2004) Rejoinder to Carlo Ratti, Environment and Planning B: Planning and Design, 31: 501-511.

ISLAM, M. Z. (2008) Children and urban neighborhoods: Relationships between outdoor activities of children and neighborhood physical characteristics in Dhaka, Bangladesh, Unpublished PhD thesis, North Carolina State University.

MILLER, H. J. (1999) Measuring space-time accessibility benefits within transportation networks: Basic theory and computational procedure, Geographical Analysis, 31(1).

TURNER, A. (2007) New Developments in Space Syntax Software, Proceedings of the 6th International Space Syntax Symposium, Istanbul Technical University, June 2007.

About the Author:

Bhuyan, Md Rashed is an architect, urban designer and researcher. Currently, Bhuyan is a PhD research scholar in the Department of Architecture at National University of Singapore (NUS). He is also a Lecturer in Architecture (on study leave) in the University of Asia Pacific (UAP), Dhaka.