The issue with the use of central jail area exposes our short memory. Sir Patrick Geddes— the father of modern town planning, advocated creating a park on the freed land in 1917. In fact 1959, 1981 and 1997 plans for the city of Dhaka did suggest the same. As the much-hyped DAP (Detail Area Plan) based on the last Dhaka Structure Plan is there, it is only justified and legal to see that regarding the use of this valuable land. There was a public presentation of draft DAP in 2007 September at RAJUK. Keen to voice a citizen’s conscience, I was dismayed to see that the consultant had proposed commercial uses on the said land, even asserting that it has no historic value. It was instantly opposed in favor of keeping it as a much-needed open area for the Dhakaites, which should have later been adopted in the revised final version.

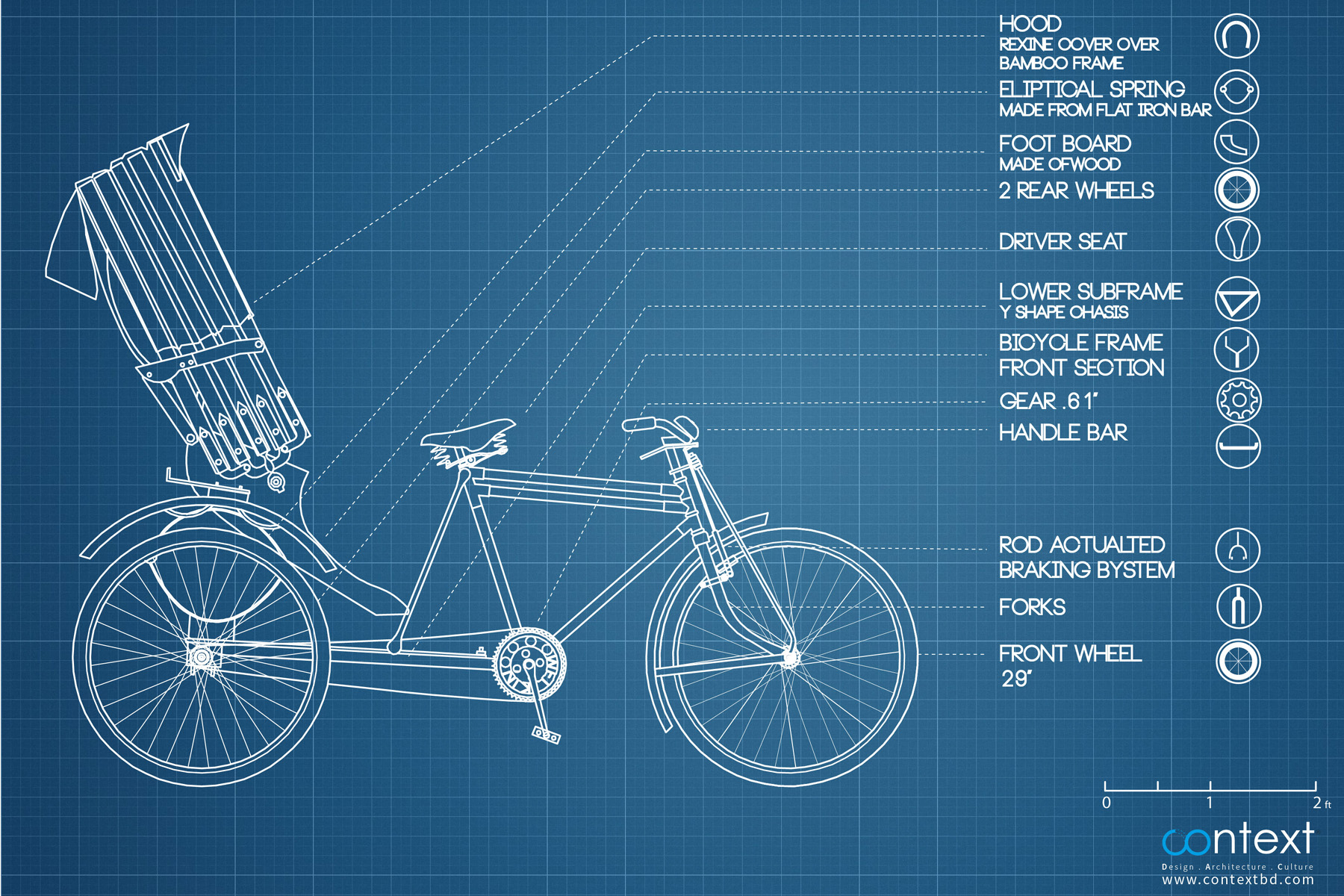

The Central Jail, originally a fort encircled by mud walls, was erected by Sher Shah on the outskirt of then city. In 1602 Man Singh set up his garrison there; his entourage settled in between the fort and the Dhakeswari Temple, in an area that was hence named as ‘Urdibazaar’. When Islam Khan stopped at Shahjadpur due to rain and flood on way to Dhaka, he sent an advance party to repair the fort in order to make it suitable for his court and residence. It is suffice to say that the central jail area is historically very important. Architecture of the Mughal secretariat including of a 40-pillar Dewani Aam, later buildings, and other important uses and historic events during the nation’s thrust towards Independence, have been elaborated in my book ‘City of an Architect’.

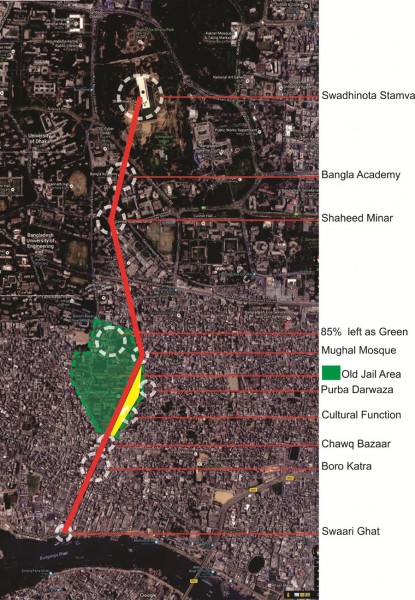

The most befitting reuse for the central jail area has been a popular architectural exercise in different architecture schools of the country. One of my friends in 1983 took this as his thesis and proposed a low-rise mixed use in an intimate scale that we usually associate with old Dhaka. Five years later, another architecture student took up the same exercise as his final project. Another attempt was made by a student under my supervision in 1992-93 at BUET. His daring and exciting proposal with symbolic contents was surrealistically simple. It had two bold premises and the postulations thereof, connecting old Dhaka with the new with an axis through the land. The axis originated at Swaari Ghat, connecting the Chawk (originally an open plaza surrounded by important structures like the fort and mosque) through the Bara Katra. On the other end of it via the Kendriyo Shaheed Minar was a point in Sohrawardi Udyan where the Swadhinota Stamva now proudly stands.

The axis represented the city—starting from when it became a capital for the first time and till 1971. Islam Khan in 1610 landed near the Ghat (Pakurtuli at Babubazaar area), paraded by the outer periphery of the city, and reached the old Afghani Fort. This will seperate 85% of the land on the west, which he proposed to keep green, from the more historical east part with Purba Darwaza as a formal entry. This part had a mix of small-scale civic-cultural uses. The statement the proposal made was bold and definite, and unseen for years in a project at this level in any architecture school in Bangladesh. The highly appreciated project was exhibited at the Shilpa Kala Academy. But all such proposals, many of which are valuable and posses a high level of practicality in directing towards enhancing the amenities and livability of the city, are never taken up to be implemented.

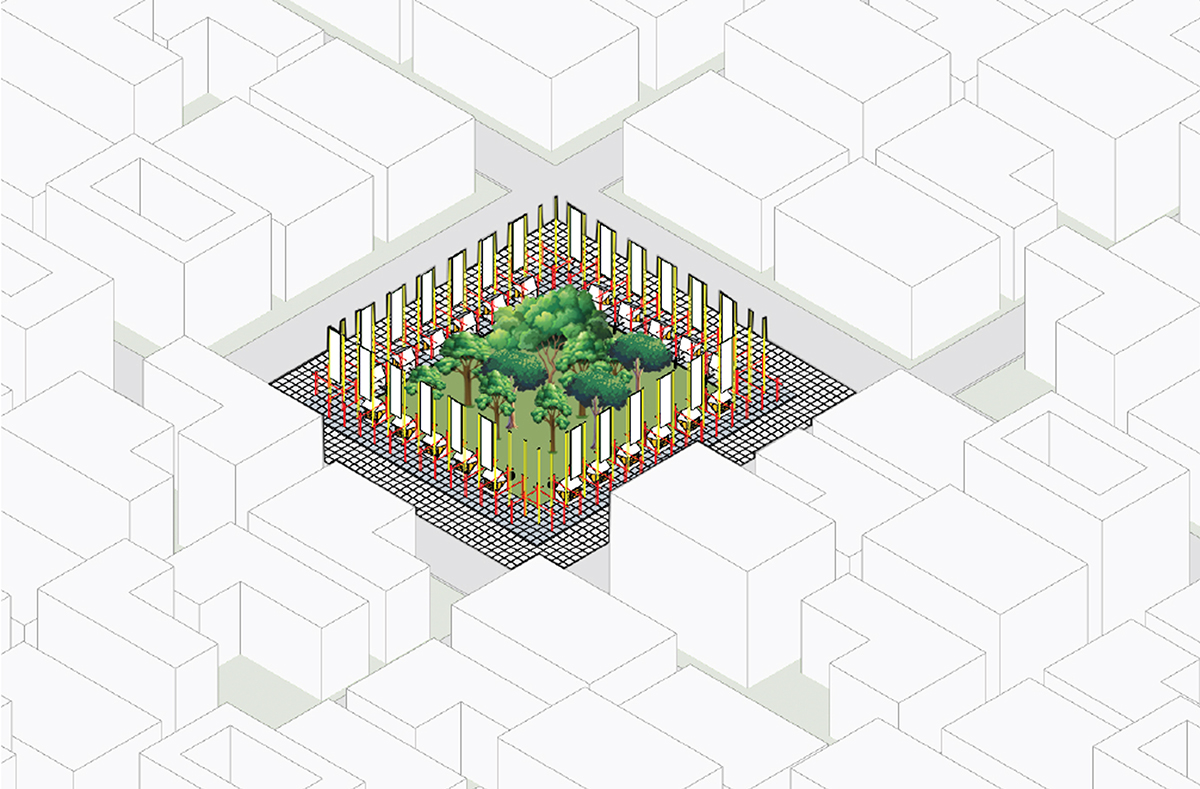

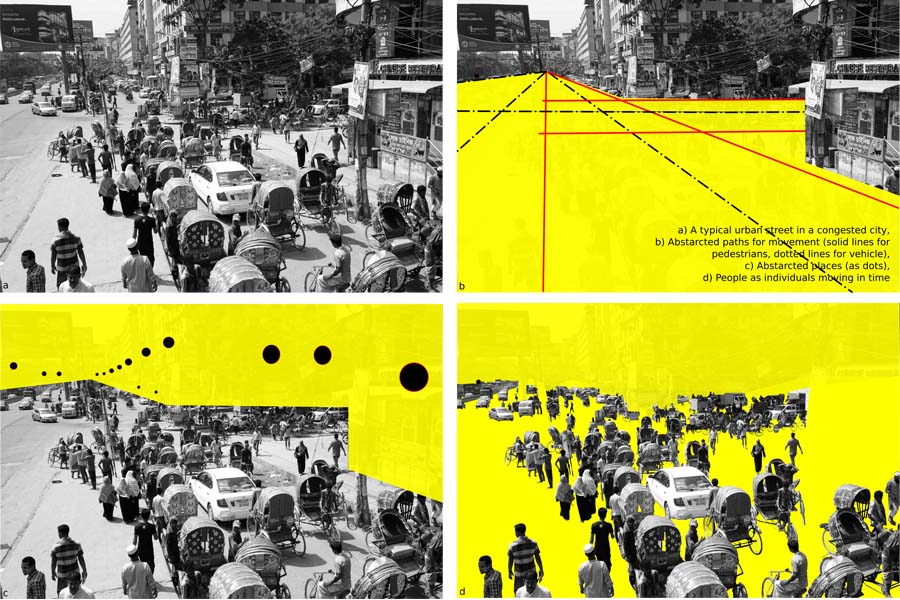

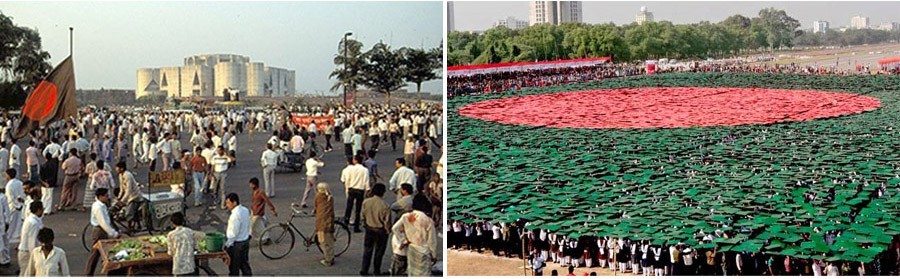

Public spaces, important assets to our cities, provide people opportunities to come together and engage with the community. Successful public spaces are inclusive of the diverse groups cities have, creating a social space for everyone in the society to participate in. Many human geography scholars have explored the interactions people have in the public space like city squares, the social networks, and the connection they form with the space. Having social events like music concerts or projecting sporting events on large screen are also a great way to get people to engage with one another— forming a sense of ‘togetherness’ in the space. This is a powerful way to create more positive environments for people to assimilate and come together as a society.

There are enough data to support the need for public spaces that improve the lives of city dwellers in many ways, like improving health, bringing people together, and offering places to break the stresses of urban life. Local economy also improves if public spaces are designed right as more people gathering means increased trades at nearby retail establishments, restaurants and coffee shops. But cities like Dhaka, one of the worst livable in the world, have instead ignored the urbanites’ need of better public spaces. For Dhakaites, access to public spaces isn’t just an incentive, it’s a right too. These spaces need to be safe, and offer a connection to nature. In fact, spaces offering this connection are often the most successful, bringing out higher numbers of visitors. Most livable cities like Vancouver and Calgary have done great at having public spaces to let users seek out the best of nature without leaving the city. Above all, our health and that of our cities depend on it.

As contexts change over time, use of this core city land need to be carefully re-examined and a proposal be made and executed, considering the history of the land, morphology of the surrounding area and its impact on that, and need of the Dhakaites. More importantly the site provides an opportunity of life time to do something for the city that its citizens can be proud of. We have wasted such other opportunities with part of the old airport or the Shangshad Vaban area. Here I could write several paragraphs or cite statistics in favor of having more public open spaces in Dhaka. But reading of Morshed in Daily Star on 27 August would suffice. Below is an excerpt from his thought provoking write up— “Can city design prevent terrorist attacks?”

“The city’s young needs playfields to exhaust their energy. How serious are urban administrators in Bangladesh about preserving neighborhood playgrounds as a way to keep the youth engaged with city life and away from the dark underworld of nefarious indoctrination? About 52 out of Dhaka’s 90 wards (60% of metropolitan area) have no access to parks or playgrounds; only 36 have some open space ranging between 0.01-0.21 acre per 1000 population. Have we thought about how neighborhood playfields would help create more Shakib al-Hasans and less Nibrases?

Where are our plazas, piazzas, malls, and maidans? Public places are where democracy finds a voice and a physical presence. Cities in Bangladesh have been experiencing unprecedented population surge. The demand for urban land is skyrocketing, leading to misguided policies of gentrification and a mastani culture of land-grabbing. Experts recommend that a livable city should have a minimum of 25% of its area as open space. Dhaka’s open space of only about 14.5% is rapidly shrinking. Research has shown that without adequate public plazas—essential for a city’s democratic practices, recreation, and community-building—the antisocial instincts of city dwellers balloon.”

Now we have 25 schools of architecture with several thousand students and about 3,000 professional architects practicing in Bangladesh. Lets organize a two or three phase open urban design idea competition for both students (can be from architecture, planning, history or any background from the nearly 100 universities) and professionals (similarly could include architects, planners, engineers) or groups thereof. The first phase can be a 1-day on-site design charrette; a brief can be developed from ideas of this phase. But such brief must include a symbolic representation, iconic structures, an open area, and mixture of small scale cultural uses.

Such participatory design approach will in deed contribute to the sustainability of whatever use that would be proposed and built in the area as a result, protected by the community, and will remain as a milestone in the city’s history.

About the Author:

Dr. Mahbubur Rahman is a Professor & Dean of Engineering & Design, Kingdom University, Bahrain