Recent developments in digital game creation software have opened up new space for the creation of participatory design tools for urban design engagement. This has enabled new ways for architects and urban planners to explore digital games as a design ‘language’, to facilitate participants and designers to communicate ideas and concepts to one another. The Maslow’s Palace project takes advantage of this trend, utilising a digital gaming approach to participatory urban design to include marginalised communities in urban upgrading conversations.

The Maslow’s Palace project currently works with three landfill-based informal settlement communities in Bhalaswa and Ghazipur in Delhi and Shivaji Nagar in Mumbai. The project uses a purpose-built gaming platform to allow participants to connect with one another, share opinions and experiences on urban focused needs and problems and generate ideas for future urban development and as an analytical tool for designers at the front end of the development process.

The primary goals of the project are to explore community perceptions surrounding urban development problems; to promote participant cooperation between community members and partner organisations as facilitators through mutual understanding of urban issues and relationships and to encourage dissemination of workshop outcomes and experiences to provoke future action.

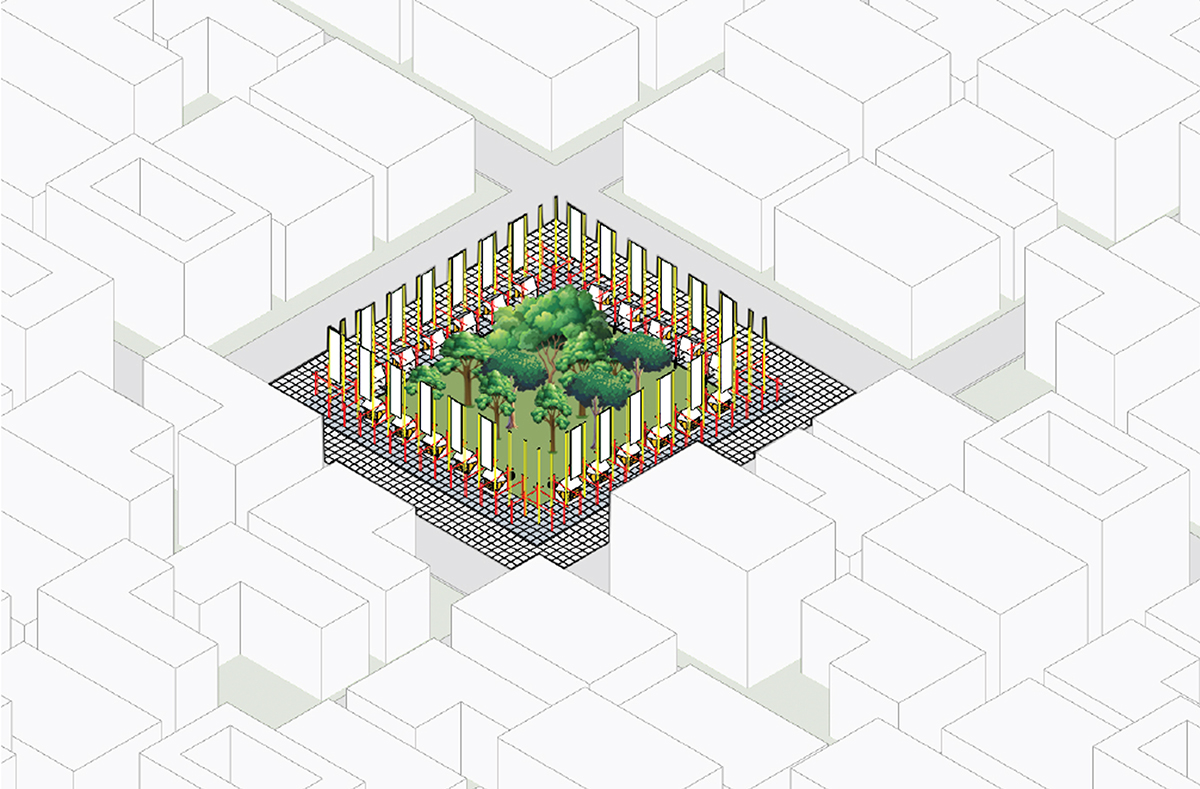

Central to the gaming approach is the concept of the “perceptual bridge”, defined by James Auger in the field of speculative design, which considers a carefully constructed balance of fictional and nonfictional urban design elements. When applied within Maslow’s Palace, fictional game elements – such as islands, explosions and fictional buildings open up new avenues for community dialogue and collaboration through temporarily bypassing existing socio-cultural structures embedded with the pragmatic requirements of the development process. The approach not only asks players to consider how things might be, but also why things are the way that they are. Nonfictional elements – such as familiar buildings, spaces and spatial relationships ensure the game play speculations and debate are grounded in reality, as well as ensuring the accuracy of in-game analytics to interface with future development processes.

Participants of the Maslow’s Palace workshops have reported gaining further understanding of each other’s perspectives and that the game made them feel comfortable expressing their opinions with each other as they knew other players would understand their points if they could communicate them visually. When conflict arose – generally around a more complex issue such as livelihood generation and security– peripheral issues or other facets of the issue were voiced and explored, allowing for players to gain a better understanding of each other’s perspectives through discussion and ideation. Fictional elements also allowed participants to pragmatic impasses that can obstruct traditional engagement methods.

Visser et al. point out that by not carefully considering people’s tacit and latent feelings and perceptions in participatory practice we unnecessarily limit designs engagement processes to “explicit and observable knowledge about contexts” and negate their ability to explore future alternatives with reference to non-physical attributes of setting (122). Digital gaming represents a promising avenue for the drawing out these important design attributes.

Works Cited:

Beattie, Hamish, Daniel Brown, and Morten Gjerde. “Generating Consensus: A Framework for Fictional Inquiry in Participatory City Gaming.” In Serious Games, 126–37. Valencia: Springer, 2017.

Johansson, Martin. Participatory Inquiry – Collaborative Design. Blekinge Institute of Technology, 2005.

Visser, FroukeSleeswijk, Pieter Jan Stappers, Remko Van Der Lught, and Elizabeth Sanders. “Contextmapping: Experiences from Practice.” CoDesign: International Journal of CoCreation in Design and the Arts 1, no. 2 (2005): 119–49.

About the Author:

Hamish Beattie the founder at HeardSpace – an urban development focused design collective and designers of Maslow’s Palace (2017). Hamish is a lecturer in Design Ethnography and PhD (Architecture) candidate from Victoria University of Wellington, New Zealand. His doctoral research investigates how digital participatory design strategies can strategically enhance empowerment of waste picker communities in Delhi and Mumbai. He has worked with the United Nations Human Settlements Programme in Nairobi, Kenya on the Block by Block programme to deliver public space and urban infrastructure projects. He was also a 2014 New Zealand Institute of Architects Design Awards finalist.

CONTEXT Contributor: ,Shuva Chowdhury | Architect, Faculty Member (AIUB) and PhD Researcher (Victoria University of Wellington, New Zealand)