The Moongrove Garden – at the tide country where man meets the mangroves

|From the Researcher|

Abstract

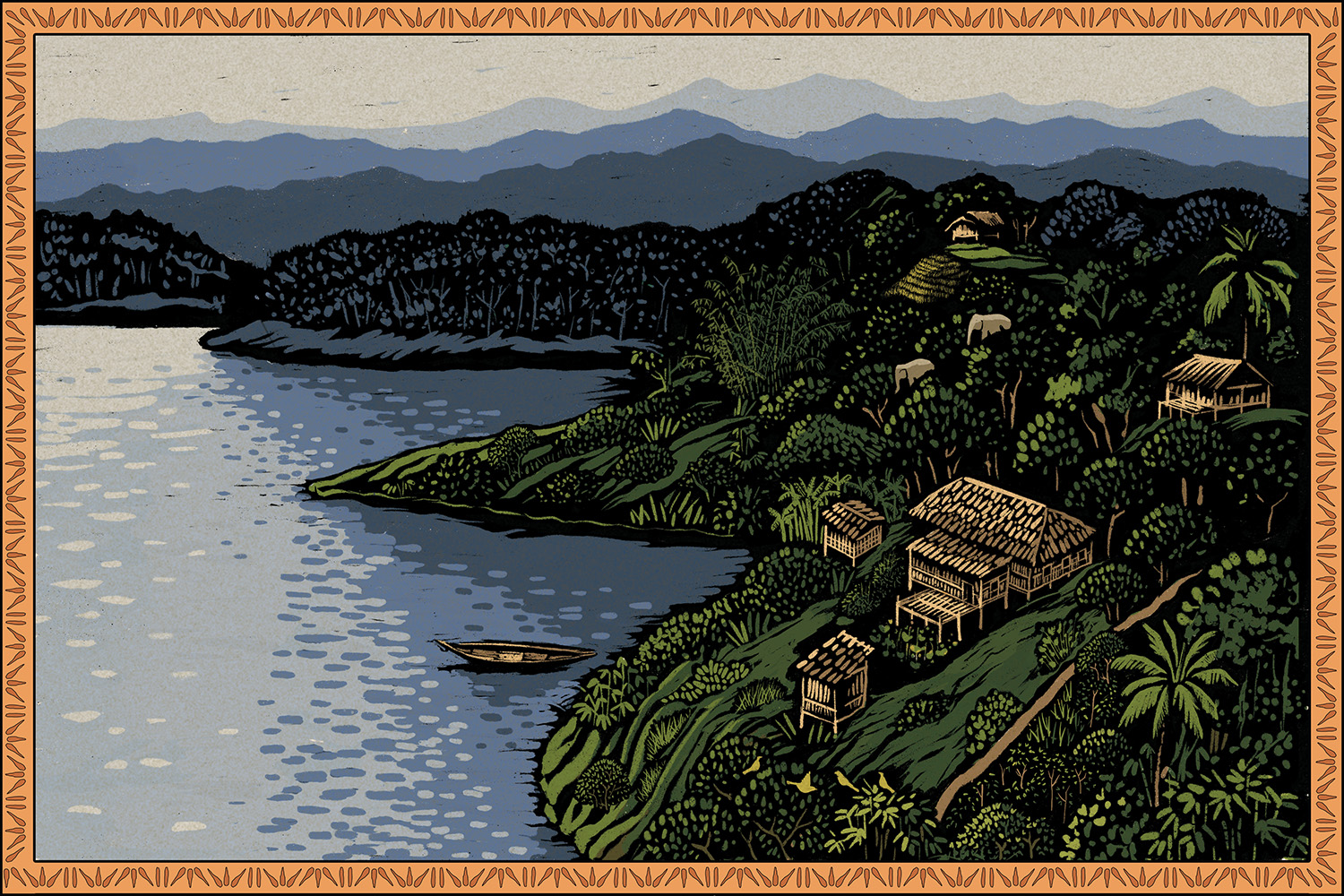

The coastal human forest interface of the Bengal delta is locally called ‘The Country of Tides’, where an inhospitable saline land of mangrove meets manmade freshwater landscapes in the fractal matrix of countless rivers and channels that are fed by brackish moon tides. To ensure a flood and saline free inland, people had to create control over this landscape and as a result, the interface is divided into polders and forests today. But in this archipelago of loam clay, which is a hotspot for a range of ecological, geomorphic, and cultural diversities, is the answer to the question of how ‘Man Should Meet the Mangroves’, that simple?

People of this area believe in a guardian goddess, who does not belong to a temple. The goddess ‘Bonobibi’ was born in Mecca and was sent to this tide country to maintain the harmony between man and nature. The myth exceeds the borders of polders, extends towards the forests, and has been surprisingly successful in creating a strong communal existence.

Man stopped capturing new forest lands long ago and locked themselves inside the polders, but the rivers still continue to erode and deposit at the polder outsides. Therefore, lands are created in between forests and polders which do not have any clear law about who do those belong to. Mangrove tries to migrate into these parts by sending over floating germinated seeds; while man tries to take control by creating saltwater shrimp ponds.

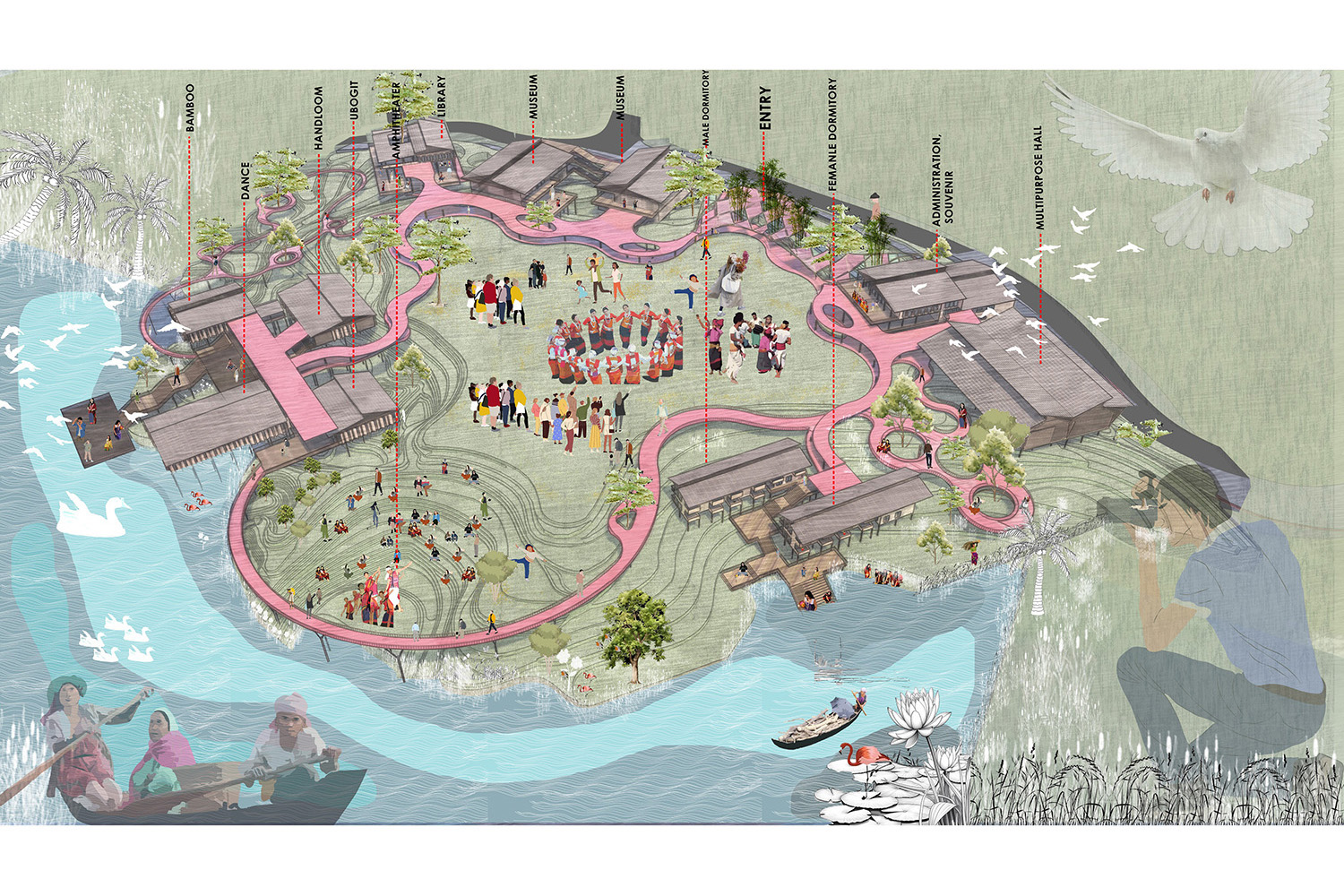

The project is a garden for the community in one of those ‘Lands without an owner’, where man meets the mangroves and the goddess without a temple tries to create a balance between them by sending over the moon tides.

The Bengal delta is an estuary where the accumulation of water from different sources, especially precipitation from the Himalayas runs over a flat plain and meets the Bay of Bengal. Before meeting the sea, the rivers have to pass through an archipelago of loam clays and mangroves. There lies the Sundarbans with its protector tigers and crocodiles.

The coastal human forest interface of this area is locally called ‘The Country of Tides’, where the inhospitable saline land of mangrove meets the manmade freshwater landscapes in the fractal matrix of countless rivers and channels that are fed by the moon tides. To ensure a flood and saline free inland, people had to create control over this landscape and as a result, the interface is divided into polders and forests today. But in this archipelago of loam clay, which is a hotspot for a range of ecological, geomorphic, and cultural diversities, is the answer to the question of how ‘Man Should Meet the Mangroves’, that simple?

The mythical belief of this area has been surprisingly successful in creating a strong communal existence among the Hindu and the Muslim inhabitants. The guardian goddess ‘Bonobibi’; according to the belief, was born in Mecca and was sent to this tide country to maintain the balance between man and nature. The myth is deeply rooted in the history of early arrival and settling of the Muslim preachers in the Bengal and it is a derivative of people’s struggle to survive in a hostile land. This unique belief gives a powerful notion of a space, which ties up two different religions through the landscape. The subcontinent has seen examples of Islamic gardens and it also used to have Hindu sacred groves from very past already but has seen none of it merged into another. When both of the types mentioned can be considered as attempts to mimic heaven or unearthly pleasure, the myth of ‘Bonobibi’, who belongs to the land and tide, not in an enclosed temple; consistently sticks to the exchange of dialogue between man and nature in the harsh real world.

The mixed diurnal brackish tide that changes salinity every season shapes landscape of both man and mangrove here. Inside the forest, it creates ecologies of the canal, mudflat, ridge, and swamp basins where mangroves with knee, stilt, buttress, and plunk roots stand. Salinity and local elevation create variation in patch formation by species with different salt tolerances. And in the inland parts, polder embankments are made to control the tides from inundating inland to stop the saltwater intrusion. In this landscape, water management such as reserving freshwater from monsoon tides, controlling inland canal irrigation, and closing the sluice gates based on salinity level needs collective decisions.

© Ahmed Faisal

Man stopped capturing new forest lands long ago and locked themselves inside the polders, but the rivers still continue to erode and deposit at the polder outsides. Therefore, lands are created in between forests and polders which do not have any clear law about who do those belong to. Mangrove tries to migrate into these parts by sending over floating germinated seeds; while man tries to take control by creating saltwater shrimp ponds.

© Ahmed Faisal

The project is a garden for the community in one of those ‘Lands without an owner’, where man meets the mangroves and the goddess without a temple tries to create balance between them by sending over the moon tides. Seen from a strategic point of view, the project in one hand will belong to the community, which means lesser chance of being occupied by the shrimp industries, and on the other hand it will use mangroves as garden patches which will mimic part of forest ecology. The design will create public spaces inspired by local beliefs and farming methods and it can be seen as a pilot project for lands of this typology along the coastal human forest interface.

© Ahmed Faisal

The site is a natural elbow-shaped land that has been used by the small farmers for seasonal rice and shrimp farming. Being in close proximity to the forest and subjected to regular tidal inundation it has a canal, mudflat, and ridge structures that are occupied by thick patches of Nypa palm, a pioneer species of the mangroves. The basin part is sunken and the lowest elevation is almost equal to the river neap tide water level. Tracing satellite images of the local elevation shows a common path of water flow in the inland. The lowest part of the land at the south side is dug and the local dike is breached in the proposal so that the tides can come inside. The tides enter through a mudflat, then go to a tidal pond through a sluice gate, and from there the freshwater and saltwater is separated and goes to different destinations.

The embankments guide to public spaces which become gradually more constructed and controlled following the existing shallow slope of the site from southeast to northwest. The lowest elevated part’s public space is mostly mud and gives an informal expression while the highest elevated part is for more formal gatherings which are more built. The tidal pond works as public space which is in between informal and formal and the rest of the land follows the existing grid of dikes and becomes farms. Finally, at the edges, the existing dike becomes a paved walkway and, in some parts, exaggerated shapes of local elevations are planted with patches of mangroves to mimic the ridge morphic ecological profile of the forest.

During a site visit (Dec-Jan 2019-2020) and after talking to experts who have been actively involved in the polder management and development programs it came out that the people are slowly rejecting salt water shrimp farming and becoming more adaptive to improvised traditional agriculture techniques introduced to them by different government initiatives like the Blue Gold Program. It was also very much clear that the communities with strong bonding are doing better practices. Shrimp farming is more profitable but needs bigger investments and the profit goes to only individual company owners; and on the other hand, communities who have been able to stop the aggression of the shrimp industry were producing crops all year around and earning more than what they would earn as shrimp farmers.

© Ahmed Faisal

This became a pull factor to shift the focus of the research toward the cultural history of the local community and local farming techniques. Besides, the research area is always seen through lenses of disaster management, ecological conservation and afforestation. This project tries to put a spotlight on the cultural history and practices of this region as well as digging out some exotic spiritual mythical connection of the periods of the arrival of Islam in this part of the subcontinent and trying to conceive the indigenous domain within the design exercise.

© Ahmed Faisal

Image Gallery: